When God Looks Angry

When God Looks Angry

When God Looks Angry

🕯️ Sitting with the hard stories until love comes into focus

There are parts of the Bible that stop us cold. Stories that leave a lump in the throat and a question we don’t dare say out loud: How could a loving God do that?

- A flood that drowns the world 🌊

- Cities reduced to ash 🧱🔥

- Entire nations—men, women, children, even animals—wiped from the earth ⚔️

If you’ve ever read those passages and felt sick or confused, you’re not faithless. You’re human.

These are not simple stories. They are stories of horror, grief, and judgment. They tell of a God who seems, at times, terrifyingly severe. And if we’re honest, we don’t know what to do with that.

Don’t rush to fix it. Sit with it. Let the ache ask better questions: What kind of love is this? What could drive a Creator to such desperate measures?

Because faith isn’t born in easy answers. It’s born in the tension—in the ache between what we see and what we still believe about who God truly is.

💠 The Hand Behind the Havoc

When we step back from the horror, a larger story begins to come into view. The Old Testament isn’t the record of an angry God losing control—it’s the story of a Father fighting for the survival of His children.

The world of Noah, Abraham, and Moses was not peaceful or kind. It was soaked in blood—filled with child sacrifice, warlords, cruelty, and corruption so deep it poisoned everything it touched. Generation after generation drifted further from the One who gave them breath, and violence became their native tongue.

So God acted. He separated light from darkness, called out a people for Himself, and set boundaries to protect the fragile hope of redemption. When the waters rose in Noah’s day, it wasn’t blind rage—it was heartbreak. When nations fell under judgment, it wasn’t revenge—it was rescue.

Every command, every act that seems so fierce, was part of a Father’s fierce love—love that protects, love that preserves, love that refuses to let evil consume what is still good.

The same God who later said, “Love your enemies,” was already fighting to make that command possible—to keep alive the lineage through which perfect love would one day enter the world.

💔 The Grief of a Father

“The Lord regretted that He had made man on the earth, and His heart was deeply troubled.” (Genesis 6:6)

Those words aren’t about a God who realized He made a mistake—they reveal a Father whose heart was breaking. He wasn’t sorry that He created humanity; He was sorrowful for what sin had done to His children. He grieved the violence, the cruelty, the corruption that filled the earth—and the terrible cost of what must come next.

When we picture God sending the flood, we often imagine wrath. But maybe the truer image is a Father standing in the rain, heart shattered, knowing that love sometimes demands what it most despises. The flood wasn’t the rage of an angry deity—it was the heartbreak of a loving One.

🛡️ Love That Disciplines

Any parent who has ever had to discipline a child severely understands that ache. You don’t do it because you hate them—you do it because you love them too much to stand by and watch them destroy themselves. You see the danger they can’t yet see. You know the pain they’re walking toward. And something deep inside you says, No, not my child.

So you draw a hard line. You raise your voice. You take away what they cherish most. Sometimes, you even take a belt to the backside—not out of rage, but out of heartbreak. The sting isn’t punishment for punishment’s sake; it’s meant to stop something far worse before it takes root. The pain is intended to prevent destruction—not as an act of anger, but as an act of love.

And you know, as you do it, they’ll see you as cruel. You’ll watch tears spill and hear words you wish you could unhear, and every part of you will want to stop. But you don’t—because love that never corrects isn’t love at all. It’s easier to be liked than to be right, but a father’s love chooses what’s needed over what’s easy.

That’s the pulse behind divine judgment. It’s not the fury of a tyrant—it’s the heartbreak of a Father. Every act of discipline echoes the same cry: “If only you would turn back to Me.”

But love could only discipline for so long. To finish the story, love would have to descend.

Love didn’t change between the flood and the cross — it simply took on flesh. ✝️

🌧️ The God Who Entered the Flood

The story of the Old Testament is the story of a Father doing everything He can to save His children from themselves. But when warnings, prophets, and judgments could no longer reach us—when sin had woven itself too deeply into the fabric of humanity—He did the unthinkable.

He stepped in. He didn’t shout from heaven anymore; He came down into the storm. The Word became flesh and walked among us. The Judge became the judged. The Creator entered His creation to bear the very curse that broke it.

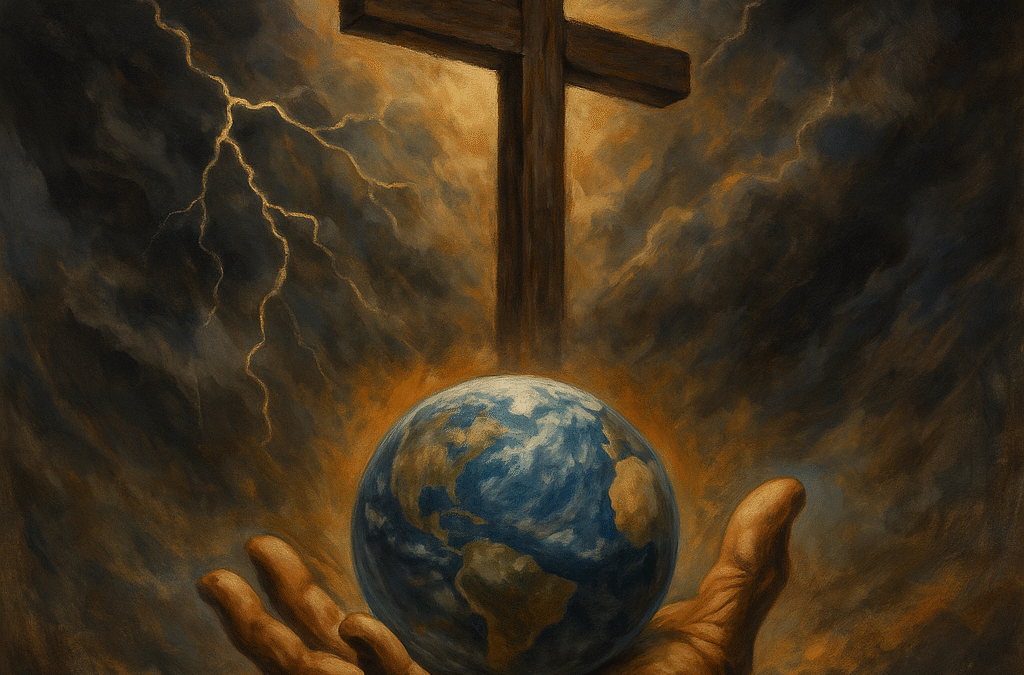

It’s as if God Himself stepped into the floodwaters—not to destroy, but to drown with us, to raise us back to life in His own resurrection. Love that once stood outside the ark now became the ark. The same hands that once shut the door now stretched wide on the cross to say, “Come in.”

The Father who once grieved over a world too far gone was now hanging in its midst, absorbing its violence, its hatred, and its sin. The same heart that wept before the flood now bled for the world it could not stop loving.

What we see in Jesus isn’t a different side of God—it’s the completion of the same love that has always been. The storm of wrath and the flood of mercy meet in Him. And when it’s over, all that remains is grace.

⛓️ The Horror That He Chose

The story of God’s love reaches its climax on a hill called Golgotha. The sky went dark. The earth shook. The Son of God hung between heaven and earth—mocked, bleeding, abandoned. The cross was not a gentle scene. It was horror. Torture. Injustice at its worst.

And yet, in that horror, “God was in Christ, reconciling the world to Himself.” He didn’t send someone else to take the pain. He came Himself.

The God who once grieved over the flood—the One who watched His creation destroy itself—stepped into its ruin. He took the weight of all our violence, all our rebellion, all our heartbreak—and He let it crush Him. Every act of judgment we fear in the Old Testament found its fulfillment there, in the broken body of Love.

Because that’s what God has always done. He enters the mess. He absorbs the pain. He bears the consequence. He doesn’t stand above the suffering of humanity—He steps into it to bring us home.

And that’s what He’s still doing now. Wherever shame, confusion, or doubt live—He’s there, reconciling the world to Himself. Even now, in your story, in mine, in every place that still feels like judgment, His mercy is at work.

The cross was not the end of wrath; it was the beginning of restoration. 🌿

🔭 Looking Back — and Forward

We can’t dismiss the terror of history. The flood, the fire, the wars—they still stand as monuments of pain and warning. But they are also mirrors. Because these stories were never only about them. They’re about us.

Every age has built its towers, drawn its swords, and filled its own earth with violence. Every heart has known rebellion, pride, and selfishness. And every one of us has needed the same mercy that washed over the world in those ancient days.

The story of the Old Testament is our story—humanity trying and failing to live without God, and a Father refusing to give up on His children. And then came the Cross.

There, in one breathtaking act, all the sorrow of history and all the judgment of sin met their end. The wrath, the regret, the grief, the flood—it all converged on that hill. And Love Himself absorbed it.

At the cross, God looked upon the chaos of creation—and made it perfect again. Somehow, somewhere, sometime, in ways we can’t yet see, “It is finished” wasn’t just for that day. It was for all of time.

No one is left out. No one is abandoned. The God who once wept over the flood now reigns from the cross—reconciling, restoring, redeeming—until everything broken is whole again. ✨

📖 The Story of Redemption

The entire Bible, taken as a whole, is a story of redemption — of people just like us who have sinned terribly against God, against others, and against ourselves. It’s the story of a God who loved us before the foundation of the world. Like birth, it’s painful and complicated and bloody — but like birth, it ends with new life. 🕊️

We will be born again. We will see the Father’s face and finally understand love in a way we can’t imagine now. We know through Peter’s words that Jesus slipped back through time and ransomed those who could have been lost. And today, in this moment, He has stepped into my time — rescuing me from myself, from my own sin, from my own chaos. ⛓️❤️

I can’t make God like me. I don’t even want a God I can manage or fully comprehend. He’s outside my world, above my thoughts — yet still, He enters my world, slips into my shoes, takes my hand, and leads me where only love can lead.

That’s my God — amazing, fearsome, and wonderful. ✨